English 1102

Dr. Tejada

21 April 2009

The war-torn nation of Afghanistan has been bombarded with multiple governments in the past thirty years. The citizens prospered until the early seventies only to be beaten down by the Soviet invasion at

the end of the decade. The Soviets abandoned Afghanistan after the fall of the Soviet Union in 1989, and as a result, many civil wars ran rampant throughout the country. Because of the incredible state of disorder, the Taliban easily took over in 1996. The Taliban established an entirely new type of government in Afghanistan that ruled the country absolutely by the laws of Islam. Not only did the Taliban strictly follow Islamic law, they took it to an extreme the nation had never seen before and oppressed the people for almost ten years. After the United States overthrew the Taliban in 2003, the citizens began to speak out about their oppression, often through the use of films. Due to the Taliban’s strong ties to Islam, many of the films portray the effects of the extreme Islamic influence in their society.

the end of the decade. The Soviets abandoned Afghanistan after the fall of the Soviet Union in 1989, and as a result, many civil wars ran rampant throughout the country. Because of the incredible state of disorder, the Taliban easily took over in 1996. The Taliban established an entirely new type of government in Afghanistan that ruled the country absolutely by the laws of Islam. Not only did the Taliban strictly follow Islamic law, they took it to an extreme the nation had never seen before and oppressed the people for almost ten years. After the United States overthrew the Taliban in 2003, the citizens began to speak out about their oppression, often through the use of films. Due to the Taliban’s strong ties to Islam, many of the films portray the effects of the extreme Islamic influence in their society.In looking at Afghan films, one must realize that the Taliban destroyed nearly all the films produced in Afghanistan before 1996. Upon taking over the country, they rummaged through and destroyed the majority of films that they found, as well as the cinemas that showed them. They claimed that films brought unclean thoughts to the minds of Muslims. Therefore, no one produced films until after the Taliban fell in 2001. The Taliban claimed to form their rules from the Qur’an, but other strongly Islamic cultures did not follow the extremes that the Taliban demanded.

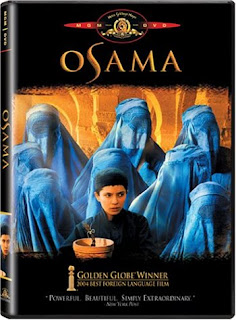

The most common theme throughout the films created since 2003 is how the Taliban affected the people. These films mainly focus on the oppression of women simply because they were the most dramatically affected. "Osama," directed by Siddik Barmak, was one of the first films to be created after the liberation of Afghanistan and clearly illustrates the effects of the extreme Islamic rulers. “Osama” follows a young girl after the death of her father and brother. Since there were no men left in the family, her mother cuts off her young daughter's hair to make her look like a boy. By doing this, Osama can escort her mother to her job at the hospital and when the Taliban shut down the hospital, she was able to acquire her own job. However, the Taliban forces her to attend a military school, thinking that she is a boy. Eventually, they discover her true identity and her punishment is living with an old man as his wife rather than being executed. The film mirrors the common day-to-day life of “…Afghani women whose right to exist was all but denied in the name of God” (Dargis).

The first scene exemplifies how the laws to which the Taliban subjected women directly affect them. In this scene, w

omen peacefully protest in the streets for their right to work, which has been denied. The Taliban quickly arrive and the women immediately flee. This scene opens up a film that “paints a depressing dystopia where the word of God is used like a bullwhip on the backs of women.” The scene explains the intense fear that the women have of their oppressors and why that fear exists. The film depicts how the Taliban outlawed jobs for women, saying that the act went against Islam, and also how the women tried to oppose this law. Also, the burkas women are required to wear symbolize the religious oppression felt by the women. Though women in other Islamic nations wear burkas, none are required to wear them except under Taliban rule. Also, under Taliban rule, the burkas had to cover the entire body of a woman and ultimately “erase her female personhood”(Golbahari) . One specific scene in “Osama” emphasizes the result of displaying too much skin. Osama’s mother rides on the side of a bike and her dress accidentally rides up to show her whole foot and part of her ankle. As the camera zooms in to show just her revealed foot, the audience hears the voice of a Taliban religious police saying “Cover your foot. Do you want men to be aroused?” This seemingly simple interaction causes the boy escorting her to refuse to do so the next day- his fear of the Taliban is that great.

omen peacefully protest in the streets for their right to work, which has been denied. The Taliban quickly arrive and the women immediately flee. This scene opens up a film that “paints a depressing dystopia where the word of God is used like a bullwhip on the backs of women.” The scene explains the intense fear that the women have of their oppressors and why that fear exists. The film depicts how the Taliban outlawed jobs for women, saying that the act went against Islam, and also how the women tried to oppose this law. Also, the burkas women are required to wear symbolize the religious oppression felt by the women. Though women in other Islamic nations wear burkas, none are required to wear them except under Taliban rule. Also, under Taliban rule, the burkas had to cover the entire body of a woman and ultimately “erase her female personhood”(Golbahari) . One specific scene in “Osama” emphasizes the result of displaying too much skin. Osama’s mother rides on the side of a bike and her dress accidentally rides up to show her whole foot and part of her ankle. As the camera zooms in to show just her revealed foot, the audience hears the voice of a Taliban religious police saying “Cover your foot. Do you want men to be aroused?” This seemingly simple interaction causes the boy escorting her to refuse to do so the next day- his fear of the Taliban is that great.At the school which Osama must attend, “the boys are of course instructed in Islam at its most fundamental, in the religious and the social modes” (Kauffman). Not only does the Taliban simply round up the boys of Kabul without prior notice, they force the boys to attend a religious school which doubles as a place for them to learn the basics of the military. The mullahs instruct the boys in the Qu’ran as well as other areas. The scene in which the mullah teaches the young boys how to cleanse themselves after having nocturnal emissions exemplifies the religious teachings at the school. Though the plot barely moves throughout the scene, it lasts for over five minutes. The mullah dictates his directions to the boys several times; the repetition emphasizes how deeply religious the Taliban forced the people to become. By lengthening the scene, Barmak stresses how “Islam is being used here both as a means of spiritual elevation and as a casus belli” by the Taliban’s religious leaders (Kauffman).

After the religious teachers discover Osama’s secret, they put her on trial in front of all of Kabul. Along with her trial are two others: “a foreign photographer arrested for being a foreign photographer” and a woman buried in the ground up to her neck to be stoned to death (Schwarzbaum). Both the people on trial with her are sentenced to death, both of

which occur on-site before Osama’s trial. During her trial, the man in charge addresses the crowd as a whole. He does not address them as Afghans, but as Muslims. He does this to make them remember not the strict laws of the nation, but the understood laws of God. He charges her with having acted against all of Islam, not against the small government of Afghanistan. This way, people are less likely to rebel against the decision because they feel less pity for someone who has acted against a religion that they all practice and in which they wholly believe. After they find her guilty of her charge, they sentence her to death. However, the mullah from her school saves her life and accepts her hand in marriage. This offer seems to be preferable until Osama realizes that the mullah is one of the “religious zealots…[who] nonetheless found wiggle room when it came to sex,” (Larsen). The audience discovers that this mullah already has three wives that he has taken unjustly and whom he seriously mistreats. Osama’s sentence to marry the mullah apparently cleanses her soul against the acts she has committed.

which occur on-site before Osama’s trial. During her trial, the man in charge addresses the crowd as a whole. He does not address them as Afghans, but as Muslims. He does this to make them remember not the strict laws of the nation, but the understood laws of God. He charges her with having acted against all of Islam, not against the small government of Afghanistan. This way, people are less likely to rebel against the decision because they feel less pity for someone who has acted against a religion that they all practice and in which they wholly believe. After they find her guilty of her charge, they sentence her to death. However, the mullah from her school saves her life and accepts her hand in marriage. This offer seems to be preferable until Osama realizes that the mullah is one of the “religious zealots…[who] nonetheless found wiggle room when it came to sex,” (Larsen). The audience discovers that this mullah already has three wives that he has taken unjustly and whom he seriously mistreats. Osama’s sentence to marry the mullah apparently cleanses her soul against the acts she has committed.Even after the fall of the Taliban, its influence is still prevalent in society. “The Kite Runner,” a film made after the success of the novel by the same name, is currently banned in Afghanistan. The Culture Ministry says that “some of the film’s scenes will arouse sensitivity among some of our people" (Halbfinger). The ministry supposedly speaks of the scene in which an Afghan boy is raped by his foes. The four main characters, all children, had to be transported out of Afghanistan to United Arab Emirates after they had completed filming the scene in order to keep the children safe. No doubt that the prevalence of Islam played a large part in this deci

sion. The scene seemingly goes against what the Qur’an allows followers to view, though the film is similar to other films about the oppression of the Soviets and the Taliban. Directors say that they wish to create thought-provoking films about the history of Afghanistan, but the Ministry will only allow them to create simple love stories and comedies, not unlike those seen in neighboring Bollywood (Halbfinger). The Ministry claims that “the people of Afghanistan want to be like America or Germany overnight. They don't understand that it takes hundreds of years to become like them…to advance along Islamic lines takes time” (Hartill). Now, the banned film would be too shocking to the conservative Islam culture.

sion. The scene seemingly goes against what the Qur’an allows followers to view, though the film is similar to other films about the oppression of the Soviets and the Taliban. Directors say that they wish to create thought-provoking films about the history of Afghanistan, but the Ministry will only allow them to create simple love stories and comedies, not unlike those seen in neighboring Bollywood (Halbfinger). The Ministry claims that “the people of Afghanistan want to be like America or Germany overnight. They don't understand that it takes hundreds of years to become like them…to advance along Islamic lines takes time” (Hartill). Now, the banned film would be too shocking to the conservative Islam culture.The fundamentalist Islamic government changed the culture of the people by eliminating films, forcing the women into the shadows of the nation, and outlawing many normal behaviors- all in the name of God. The consequences of this oppression are now expressed through the use of films. However, just as the religions of a nation can change films, a film can affect the number of people who follow a religion and how closely they follow it.

Works Cited

Stanley Kauffmann. (2004, March). Islam: Two versions. Review of Osama. The New Republic, 230(8), 22-23. Retrieved April 14, 2009, from ABI/INFORM Global database. (Document ID: 617984581).

Desson Thomson. (2004, February 20). The Veiled Threat of Life Under the Taliban :[FINAL Edition]. Review of Osama. The Washington Post,p. C.01. Retrieved April 14, 2009, from ProQuest National Newspapers Core database. (Document ID: 547591061).

Manohla Dargis. (2004, February 6). Movies; REVIEW; A curtain parted in Afghanistan; A girl glimpses equality under the Taliban when she masquerades as a boy in 'Osama.' :[HOME EDITION]. Review of Osama. Los Angeles Times,p. E.3. Retrieved April 15, 2009, from Los Angeles Times database. (Document ID: 538903051).

http://www.opendemocracy.net/arts-Film/article_1769.jsp

Lisa Schwarzbaum. (2004, February). OSAMA. Review of Osama. Entertainment Weekly,(751), 56. Retrieved April 15, 2009, from Research Library database. (Document ID: 551858281).

Halbfinger, .http://www.nytimes.com/2008/01/16/world/asia/16kiterunner.html

Hartill, Lane. http://www.csmonitor.com/2004/1207/p07s01-wosc.html

Josh Larsen. (2004, March). Taliban Days. Review of Osama. The American Enterprise, 15(2), 46. Retrieved April 16, 2009, from Research Library database. (Document ID: 546209831).